home

Economy Economy

Books Books

History of the world economy - Polyak GB History of the world economy - Polyak GB

|

History of the world economy - Polyak GB

22.2. The state of agriculture

Throughout the XIX century. Agriculture remained the leading branch of the economy of Russia: at the beginning of the century the overwhelming majority of the country's residents were engaged in it - 94% and at the end of the century - 87%. The level of development of agriculture determined, thus, the welfare of almost all Russians.

Categories of peasants

The most important categories of the peasantry in the first half of the XIX century. Were peasants landlord, state and specific.

Specific peasants belonged to members of the royal family. Their number was about 2 million people. The overwhelming majority of them were on dues, which in 1830 was replaced by land collection. In addition, they paid a per capita tax.

The state peasants , who constituted about 9 million male souls, were feudal-dependent from the state. Most of the state peasants were on loan, they also paid a per capita tax. To improve the situation of state peasants in 1837-1841. Under the leadership of the Minister of State Property Count PD. Kiseleva reform of the management of state peasants was carried out. The peasant allotments were somewhat expanded, so that on average, about 5 hectares per man's soul, the peasants were allowed to lease state lands, loans to the bank. The resettlement conditions were developed for those wishing to explore new lands, primarily the southern and eastern outskirts of the empire, a system of peasant self-government, a network of schools and medical facilities. Peasants began to teach the best methods of farming, informed about new improved breeds of cattle and plants.

The state peasants began to buy land more actively than before (although they had this right along with merchants and petty bourgeois since 1801), and on the eve of 1861 there were 300,000 peasants-private land owners in Russia. In general, the state of the state peasants was more prosperous than the landlords.

Landlord peasants constituted the most numerous part of the peasantry - about 11 million male souls, a number of them during the first half of the 19th century. Practically did not change. The main elements of the portry economy continued to remain farming and peasant farming. The ratio of bar and peasant land in different regions of the country was different, but on average ranged from 1: 1 to 3: 1, respectively.

Peasants' obligations

The leading organizational unit of the peasant economy was a peasant family - a tax on which various duties were imposed. The tax was recorded by men between the ages of 17 to 55 and women from marriage to 50 years. Both the peasants and the landlords were interested in seeing that taxes were approximately equal in their productive power: it was easier to distribute duties. Fulfillment of duties depended on the provision of peasant farming with livestock, implements, labor and land. The peasant land was in the general use of the peasant community and was distributed among the farms on equalizing terms by the number of draft souls in the economy.

The most important kinds of peasant duties were corvée, which prevailed in the chernozem provinces, and the obrok, more common in the non-chernozem center. Barbchinnoye and obrochnyh economy had its own specifics.

The economic significance of the corvée economy was, first of all, that the peasants guaranteed to provide the farming economy with free working hands. The peasants were busy at the corvée on average four or five days a week (on average, from three to seven days). The evolution of the corvee system of the economy was proceeding along the path of expanding the barbarian system and reducing the size of the peasant's own stock. The size of the peasants' land plots amounted to 3 hectares for the peasant's soul, in quitrent estates - 5 hectares. In the first half of the XIX century. In the corvee farms, the monthly period began to spread -the complete liquidation of the peasant's stock and the transfer of peasants to a monthly monthly fee. The degree of economic independence of the peasants at the corvee was significantly lower than that of the peasants in the quitrent.

While in the corvee economy the main income was extracted by the landlord from the cultivation of land and agricultural production proper, the economic meaning of the vervain system was different: the income was extracted from the entire amount of economic activity of the peasants, the most important of which were the detached trades (ie, work in manufactories, artisan artels , Factories), trade, etc. Obligatory peasants, paying a quitrent (in various provinces the amount of it fluctuated in the middle of the century from a few dozen to many hundreds of rubles a year), could at their discretion dispose of the amount that remained with them. They were more independent in their economic activities than the corvée peasants; In the environment of the peasant peasantry, the processes of property stratification were faster, individual peasants were able to accumulate considerable capital, and it was the dowager peasants who had more opportunities to redeem themselves. There were cases when dowry farmers were much richer than their landlords.

However, in general, both obrokal and corvee farms did not have really significant internal growth opportunities. All attempts to improve them rested on the low productivity of serf labor, the low level of serf skills, in the impossibility of their further effective use; The overwhelming mass of serfs was not at all interested in the results of their labor. The lack of positive dynamics in the development of agriculture clearly illustrates the yield: in the beginning of the XIX century. The average yield of grain was 3.5, and in the middle of the century it was 3.6.

The main brake on the development of the agricultural sector, therefore, was the fortress system itself .

In the first half of the XIX century. Began to raise the question of the abolition of serfdom. The understanding has come that serfdom is evil, and that rejection of it is inevitable.

This position was typical for the most educated people in the country. The overwhelming majority of ordinary landowners, fearing a change for the worse and not wishing to lose free labor, spoke sharply against the abolition of serfdom.

Nevertheless, throughout the first half of the XIX century. The state authority periodically issued decrees aimed at alleviating the serfdom of the peasants and limiting the nobility's monopoly on land. The first most important were the decrees of 1801, allowing merchants, petty bourgeois and state peasants to buy in their possession uninhabited lands; Noblemen were forbidden to sell serfs without land. In 1803, a famous decree was adopted on free grain farmers, which enabled the landowners to liberate their serfs for ransom on mutually beneficial terms-a sort of first attempt at the mild liberation of serfs. It was not crowned with great success - in the first half of the century only 1.5% of the total number of serfs received freedom. In the period from 1807 to 1819 gg. Serfdom was abolished in the following regions of the Russian Empire: the Duchy of Warsaw, the Estland, Lifland, Kurland provinces, where the local nobility opposed their peasants less. In 1833, the landlords were forbidden to sell peasants from public bargaining, in 1841 - to sell peasants at retail, in 1843, landless nobles were forbidden to buy peasants. In 1844 the landlords were given the right to let the households go free to land without land, in 1847 the serfs were granted the right of redemption for freedom with land when selling the estate for the debts of the landowner.

The reform of 1861 on the abolition of serfdom

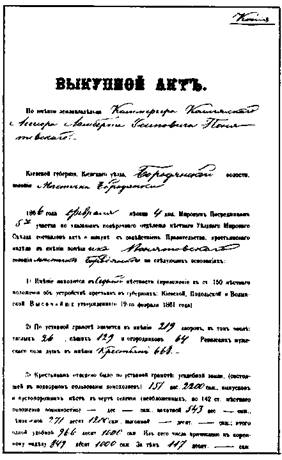

Finally, in 1861, a reform was carried out - the abolition of serfdom . The most important provision of the reform was the abolition of the peasants' personal dependence. Former serfs were now registered as free rural inhabitants, they could own and dispose of property, including land, they received freedom of economic activity and movement. Empowering the peasants with personal freedom was the most important achievement of the reform.

The issue of peasant allotments was extremely important. It was assumed that within two years after the reform, the size of allotments should be determined, which the peasants had to redeem. To clarify this, all the provinces of European Russia were divided into groups according to the level of soil fertility. As a result, in the provinces with infertile lands, the allotments of the peasants remained the same as before the reform, or even became larger-they were "cut off" with land. In the chernozem provinces with fertile soils, the peasants "cut off" part of the land. On the average for European Russia in the post-reform period one peasant soul accounted for about 3 hectares.

Their peasants had to buy out their land allotments from the landowner. The size of the repurchase was equal to the cash amount, yielding income in the amount of the previous amount of the loan, as if this amount would be put into the bank at 6% per annum (the usual interest rate at that time).

Only a few of the peasants could redeem their holdings at once, most of them did not have sufficient capital. In this case, the peasants were to pay the landowner at once only 20%, and then the mediator between the peasants and the landlord became the government, which paid the landlord the remaining 80% of the redemption amount. The peasants had to pay their debts to the government for 49 years.

Until they redeemed their allotment, they were considered temporarily liable and fulfilled certain obligations to the landowner: from the corvée peasants it was required to work from the allotment of 40 days of men's and 30 women's, and from paying - to pay from an allotment of 8 to 12 rubles. Silver per year.

It is characteristic that many peasants did not rush to redeem their allotments and did not aspire to change. This situation in the country was not satisfied with the government and in 1881 it was announced that since 1883 the ransom becomes mandatory, and the temporarily liable status is terminated. In reality, the allotments were redeemed by 1895, and the collection of redemption payments from the peasants in favor of the government was terminated already at the beginning of the 20th century, in 1905.

The reform of 1861 played an important role in the initial accumulation of capital: as a result of it, a market of wage labor was created in Russia (4 million peasants were freed without land), and capital was mobilized by the redemption operation (peasants paid three times for land by 1906 More than the land was worth before the reform). Thus, the reform created two necessary conditions for the development of capitalist production.

The post-reform period

In the post-reform period, the country as a whole accelerated the development of agriculture. To the greatest extent, this concerned private, or, as they were still called, proprietary lands. Representatives of all strata of Russian society acted as private owners, and foreigners could also purchase land. The average size of private land ownership in Russia at the end of the XIX century. Was 115 hectares per farm (for comparison: in England - 23 hectares, in France - 8 hectares, in the USA - 55 hectares).

In the movement of landed property, the main trend was noted: the peasants most actively bought the land, and the nobles sold it, in the second half of the 19th century. The size of the aristocratic landownership has almost halved. This testified to the restructuring of the country's agriculture in a capitalist way.

For agricultural production organized on private lands, there was a tendency to use hired force, to use improved tools and machines, fertilizers, including artificial ones, to produce products on the market. Thus, for the most part, these were farms that developed along the farm path.

However, private lands accounted for only a quarter of all lands involved in agricultural production. Two quarters comprised communal lands belonging not to a specific peasant, but to the peasant community as a whole: the community acted as a collective landowner.

The role of the community in the life of the peasants was strengthened after the abolition of serfdom. Without the permission of the community, the peasant could not get a passport and leave the village, could not get his property into the property and freely dispose of it. The community distributed and redistributed the land between the peasants, and the basis of its policy was the desire for equalization, equal conditions for everyone: everyone had to get a part of a good, medium and barren land. The ego led to an intersection - the peasant family could own dozens of tiny pieces in different places. The inevitable result of the strand was a forced crop rotation: the community dictated to the peasant what culture to sow in which field, determined the terms of sowing and harvesting.

The result of such organization of farming on communal lands was the lack of interest of peasants in labor, poor quality of tillage, low yield and marketability. By giving chance to weak farms to survive - freeing them for a while from taxes, helping in the processing of fields, the community held back the development of potentially strong farms. The inhibiting role of the community became so evident in the mid-nineties of the nineteenth century that the government began work on the preparation of a new agrarian reform, the implementation of which took place already in the twentieth century.

Comments

When commenting on, remember that the content and tone of your message can hurt the feelings of real people, show respect and tolerance to your interlocutors even if you do not share their opinion, your behavior in the conditions of freedom of expression and anonymity provided by the Internet, changes Not only virtual, but also the real world. All comments are hidden from the index, spam is controlled.